The BoJ is Trapped

The Bank of Japan just raised rates for the first time since 2007. Is Ueda sleepwalking into an inflation wave?

On Tuesday, the Bank of Japan finally finished its eight-year run of negative interest rates and reversed most of its unconventional monetary easing strategies, stating that Japan is approaching a new era of “stable inflation”. BoJ Governor Kazuo Ueda also stated that the bank's policies have “achieved their objectives” and discussed why the hike was justified as wages and prices are rising steadily in Japan. The BoJ is adjusting its primary goal for short-term interest rates to between 0% and 0.1%, marking its first rate hike since 2007.

In 2016, the Bank of Japan had adopted Negative Interest Rate Policy (NIRP), aiming to “stimulate borrowing and lending” to revitalize the nation's sluggish economy. This approach of negative interest rates, also used by some central banks in Europe, basically means depositors will pay fees to banks for holding their money and enables borrowers to secure loans at very low costs, thereby encouraging spending.

It is necessary in the upside down world of Japanese economics, where debt to GDP is a staggering 263% and a population bomb is ticking, with more and more seniors retiring every year paired with a plummeting birth rate. Consistent deflationary forces have been in effect ever since the 1989 bursting of the Nikkei stock bubble.

They also suppressed rates by running what is called Yield Curve Control (YCC). Rates in Japan were already low by historical standards but they were shoved down to the zero bound and kept there after the announcement of the policy.

We’ve discussed Japan’s unconventional YCC policy approach before, mainly in a post called The Japanese Maginot Line-

The policy is simple- print Yen to buy bonds to drive the yield down when yields get too high, and sell the bonds if yields get too low. By using YCC, the governor of the BoJ, Kuroda, had hoped to shift from the extremely accommodative QE to a less (relatively) easy monetary stance.

Although this policy was supposed to be “less” stimulative, it still ended up being dovish, since in effect there was a permanent bid on any JGBs. The BoJ gobbled up Japanese bonds day after day, through both conventional “fixed purchase” operations and the ad-hoc “unscheduled bond buying operations”. Both these tools were used to keep rates down, and continually run de-facto QE as a side effect.

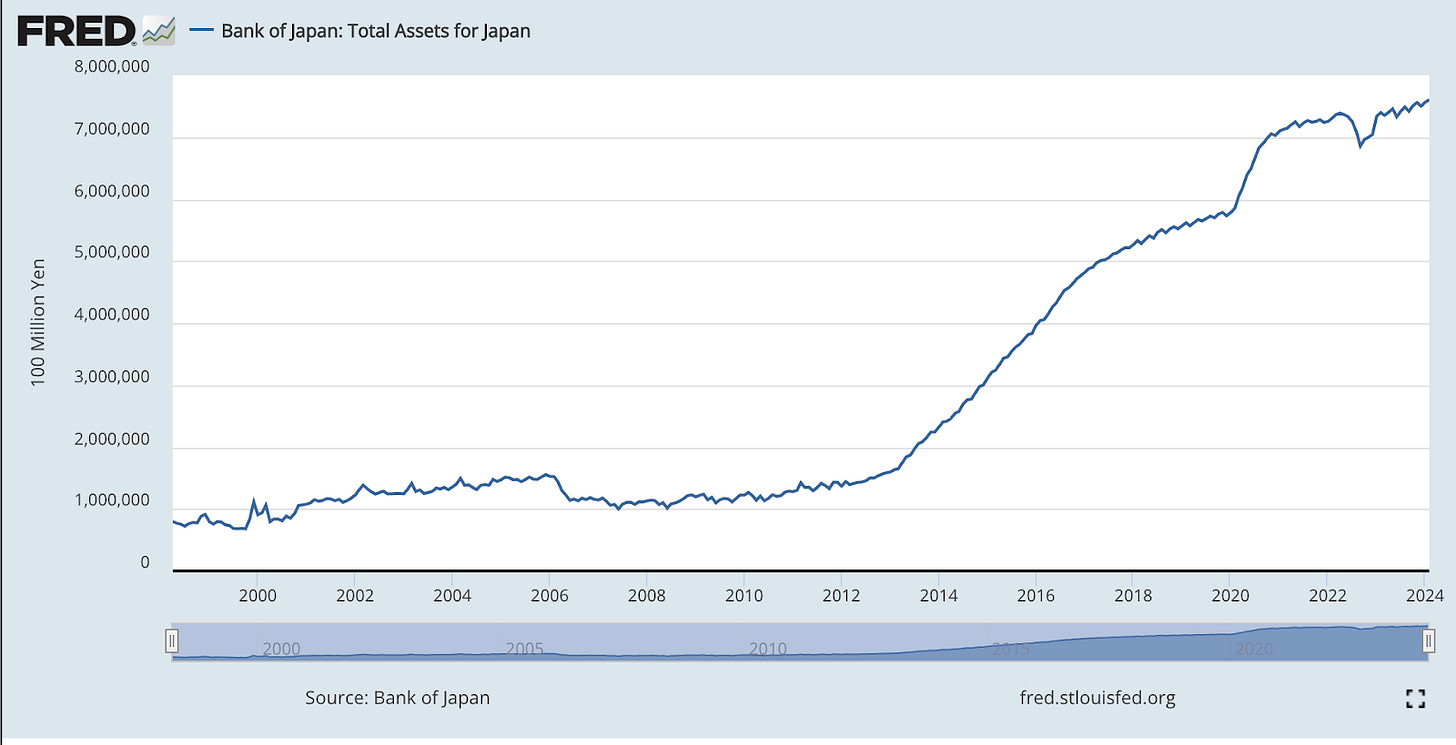

This is clearly seen in the BoJ’s balance sheet, where we can see the steady growth of assets from 2012 onwards.

Several key things happened at this time. Shinzo Abe assumed the role of Prime Minister on December 26, 2012. Soon after taking office, he unveiled his economic strategy, referred to as "the three arrows." Each arrow symbolized a component of his economic plan: the first arrow stood for monetary easing, the second for adaptive fiscal policy, and the third aimed to represent strategies for growth and structural reforms.

2012 also was a milestone in the realm of monetary objectives, with both the Fed and the BOJ embracing a 2% inflation target. However, the BOJ's commitment to this target was somewhat ambiguous at this point, as it did not specify a strict 2% inflation target. Consequently, these two central banks became part of the wider collective of central banking institutions that have adopted an inflation policy, which had been pioneered by New Zealand in 1990.

The Monetary Policy Meeting held on April 4, 2013 marked Haruhiko Kuroda's debut as the Governor of the Bank of Japan. During this meeting, something called Quantitative and Qualitative Monetary Easing (QQE) was announced. The primary objective of QQE was to attain a 2% inflation rate within approximately a two-year timeframe. The strategy was designed to combat deflation in the nation by expanding the size of its balance sheet and enhancing its quality through both "quantitative" growth and "qualitative" improvements.

Basically, this means that the bank would focus on not only buying more assets, but specifically buying more illiquid and risky assets that existed in the financial system, effectively removing these “toxic” securities from the banking system and shoring them up on the central bank’s balance sheet. This would increase risk of mark to market losses for the BoJ, of course, but this “doesn’t matter” since the Bank can always print more Yen to cover any losses.

The BoJ committed to persist with its program and to enhance it if necessary. The focus of the policy shifted from the policy interest rate (the uncollateralized overnight call rate) to the monetary base. The 2013 QQE plan entailed expanding the monetary base annually by an amount ranging between ¥60 trillion and ¥70 trillion. The main components of these purchases included:

JGBs: with a maturity up to 40 years, with an average maturity of 6–8 years (7 years).

Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs): ¥1 trillion

Real Estate Investment Trust (J-REITs): ¥30 billion

The plan was later expanded to ¥80 trillion. This program has been going on for a decade, and as a result in 2018 the assets held by the central bank grew to become larger than the Japanese economy itself!

Anyways- back to this announcement.

The Bank of Japan said they ceased its Yield Curve Control and Qualitative and Quantitative Easing policies, which included buying Exchange-Traded Funds (ETFs) and Japanese Real Estate Investment Trusts (J-REITs). The central bank also plans to gradually decrease its purchases of corporate bonds and commercial paper with the aim of phasing out these operations over approximately a year. But- and this is crucial- to counteract any potential sharp rise in long-term interest rates, the BOJ has pledged to maintain its purchases of Japanese Government Bonds (JGBs) at a comparable level to previous practices.

Winston Nakamura from Across the Spread put together a great summary of the key learnings.

So, in sum this announcement is less of a big deal than it looks like on the surface. Yes, the BoJ is shifting their monetary policy slightly, bringing up target rates on JGBs out of the negative territory, and yes, they are finally slowing down their purchases of ETFs and REITs, effectively ending support for the equity and real estate markets. But this was an obvious choice, as equity markets are already ripping upwards with the tide of global liquidity and the Bank is injecting money anyways through its scheduled bond buying operations.

And as Nakamura mentions, they are “ending YCC” only for certain securities, but de-facto they are still going to print to support their bond market to ensure rates don’t get out of control:

2) JGB Buying technically completely unchanged in practice - and (maybe?) a change in rhetoric? Not sure what they’re trying to do/are doing with the statement itself - but in practice: BOJ remains on standby to buy up to an unlimited amount of JGBs as and when they see fit. We just don’t know when and where that is ever since October BOJ in which any YCC explicit upper bound (then set at 1% on 10Y JGB yields) was removed.

So the BoJ will keep printing, rates are now not negative but also not supposed to “rise too rapidly”, and Ueda is beginning to succeed in his goal of what Nakamura terms “Yield Curve Control, Control”. This essentially means changing the definition of YCC every so often to keep the market on its toes- guessing what the next move will be.

The current account balance rate will now be targeted between 0 to 0.1%. Effectively, although the Bank does not target an upper band anymore for YCC, it will make “nimble responses” in case of a rapid rise in long-term interest rates. Again, thanks to Nakamura for this graphic.

So in reality the bank is going to continue easing, rates will still be low (although no longer negative) and inflation will continue. A large wage price spiral is in motion- last week, Japan's biggest labor union announced that major corporations intend to implement an average wage hike of 5.28% this year, the biggest increase since 1991.

There is no surprise therefore that Yen/Dollar pair has broken the vaunted 150, again. This is the key level where the Bank of Japan intervened multiple times in the fall of 2022, ultimately dumping $80B or so a month to hold the line and prevent further yen depreciation.

Many Japanese market analysts I follow are not happy with this development. They are beginning to grasp what I have been forecasting for years- that stock prices can rise, completely disconnected from the real economy. In fact, maybe equities are just front-running larger devaluations of the currency that are coming- a sign that people want to get out of cash and into an asset that will at least somewhat keep pace with the yen devaluation.

Be careful what you wish for, Ueda.

Inflation can come like a thief in the night, and if you draw down your large stash of Treasuries defending the currency- you will have nothing left.

If that happens, there will be nothing left to stop yen devaluation, and your feeble attempts to raise rates will be laughable. This change to 0.1% rates on current accounts is not enough to actually fight any inflation- you will have to grow some teeth if you want to actually accomplish anything.