The Creature from Threadneedle Street

The Federal Reserve was based on a much older, much craftier institution birthed out of war and conflict.

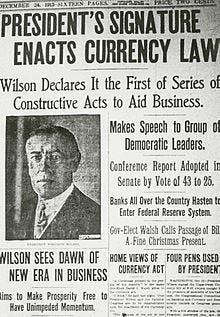

Today, December 23rd, marks the 111th anniversary of the Federal Reserve. This institution, birthed in a secret meeting on the remote Jekyll Island, was the result of years of coordination between an elite cadre of men whose influence spanned both Wall Street and Congressional houses, and had failed as a “National Reserve Association” before being passed.

Paul Warburg, one of the co-creators of the Fed, had long been an unofficial advisor to the National Monetary Commission and had published multiple papers discussing a need for a centralized banking institution. Major newspapers had published articles supporting his views, including the Washington Post article in March 1913 titled "Warburg Wants Elastic Currency," and other opinion pieces describing his speeches and writings.

There was little support for the Federal Reserve from the public, which was in the midst of the antitrust and anti-monopoly movement birthed from the excesses of the robber baron period of the late 1800s and early 1900s. The passing of the Federal Reserve act itself happened in late December- two days before Christmas, when almost a third of the Senate was absent. The effects of the Fed have been long-lasting and pernicious, but this idea was not novel- it was modeled on another much older institution, located across the Atlantic Ocean.

The Bank of England, established in 1694, stands as a monumental institution in global finance. Often hailed as the world's first modern central bank, it was born out of necessity. In the late 17th century, Britain was embroiled in the costly 9 Years War with France, and King William III was desperate for funds. The solution was a new revolutionary financial institution that would lend to the government in exchange for a royal charter (a special permission from the king, giving the Bank the power to issue money and manage the government's debt).

This concept, spearheaded by the Scottish financier William Paterson and a group of wealthy merchants, was the seed from which the Bank of England would grow. Unlike anything seen before, it allowed the government to borrow vast sums of money. While the bank’s primary role was lending to the government, it was also permitted to issue banknotes backed by its reserves, a novel idea that would lay the groundwork to the development of modern-day central banking.

It’s important to understand that the Bank of England wasn’t the first bank of its kind. Across the North Sea, the Dutch had already established the Bank of Amsterdam in 1609, as covered in an earlier piece we wrote, How The First Reserve Currency Died. However, the two institutions were fundamentally different. The Bank of Amsterdam, also known as the Amsterdamsche Wisselbank, was primarily a deposit bank, designed to bring order to the chaotic world of currency in the Dutch Republic.

It didn’t issue loans to the government, nor did it involve itself in sovereign debt management in the way the Bank of England would. Instead, the Bank of Amsterdam was essentially a clearinghouse for international trade, offering merchants a reliable and stable way to store their money and settle accounts. While it played a crucial role in stabilising the Dutch economy, its influence in public finance was limited. The Bank of England, in contrast, was born out of a need to finance the state and was designed to be a lender of last resort to the government from its very inception.

Throughout the 1700s, the British banking system evolved rapidly, with the Bank of England at its heart. Initially, its role was modest—primarily lending to the government—but as Britain’s economic and military power grew, so too did the bank’s importance. By the early 18th century, the Bank of England had begun issuing banknotes that circulated more widely, replacing gold and silver in everyday transactions. These notes were a step toward a more fluid financial system, allowing for more efficient commerce without the need for physical metals.

Meanwhile, private banks across England began to proliferate. By the mid-18th century, there were approximately 300 private banks in England, offering credit to businesses and individuals. The issuance of notes, which while not universally accepted, facilitated local trade and commerce. It also created a fragmented monetary system, where trust in a note’s value depended heavily on the reputation of the issuing bank.

SPONSOR: I’ve talked a lot about the value of Bitcoin and its use case as fiat currencies inflate away. As such, I'm proud to have Onramp as a sponsor supporting this newsletter, a firm at the forefront of pioneering a trust-minimized form of Bitcoin custody.

With Onramp Multi-Institution Custody, assets live in a segregated, cold-storage, multi-sig vault controlled by three distinct entities, none of which have unilateral control.

To learn more about Onramp's custody solutions, and financial services like inheritance planning, connect with their team or schedule a consultation. You can use this link to get a discount on their services.

Now let’s get back to it!

Unlike a standardised national currency, private notes were often accepted only locally, and may not be recognised in other regions. For example, notes issued by a small rural bank in Cornwall were unlikely to be accepted in London or even in neighbouring counties.

This lack of universality complicated trade beyond local boundaries, increasing transaction costs and slowing economic efficiency. Competition among banks also led to inconsistency of denominations with obscure note values, such as 25 shillings, which were difficult to use in transactions. Over-issuance of notes was another problem. During the financial panic of 1793, numerous private banks failed as they had issued far more notes than they could redeem in gold, triggering widespread panic and distrust.

Furthermore, the value of these notes could fluctuate based on the issuing bank's financial health, creating uncertainty. If a bank failed or its reserves were inadequate, its notes could become worthless, undermining public confidence in the monetary system. This vulnerability to bank runs and collapses made the system inherently unstable.

Decentralized banking also posed coordination challenges. Without a central authority to regulate issuance, the risk of over- or under-issuance of notes (leading to inflation) or under-issuance (causing credit shortages) was significant. Competing banks sometimes issued notes with incompatible denominations or standards, further complicating trade and bookkeeping. Merchant banks like Barings (founded in 1762) and Rothschilds (emerging as a financial powerhouse by the late 18th century) played critical roles in financing trade routes, major infrastructure projects, and Britain’s expanding empire.

The 18th century marked a transformative period for Britain’s financial system, as institutions like the Bank of England became integral to the nation’s expanding ambitions. Initially established in 1694 to finance King William III’s war against France, the Bank served as a primary dealer for government debt, raising £1.2 million in its founding year. Over time, it branched into limited commercial lending, such as discounting bills of exchange for merchants (purchasing short-term promissory notes from holders before the maturity), Merchants often needed immediate cash to fund their operations rather than waiting for the bill to mature. By selling the bill to a bank at a discount, they could access liquidity immediately. This supported Britain’s growing trade networks. By 1742, the Bank formalised these operations to stabilise markets, cementing its role in managing liquidity during crises like the 1715 Jacobite Rebellion.

The Bank’s rivalry with the South Sea Company during the early 18th century expanded its influence. Both institutions vied to manage Britain’s burgeoning national debt, culminating in the South Sea Bubble of 1720. This dazzling spectacle of financial euphoria, fuelled by rampant speculation and political manoeuvring, promised untold riches from South American trade but ended in one of history’s most infamous financial collapses, akin to the 2008 crisis. The Bank’s intervention after the bubble burst, including refinancing debts under Robert Walpole’s guidance, marked its evolution into a cornerstone of Britain’s financial stability and a precursor to modern central banking.

At its heart was the asiento, a treaty clause granting Britain the exclusive right to supply enslaved African laborers to Spanish colonies. This grim contract, bolstered by promises of unrestricted trade, gave the illusion of unlimited opportunity in a region mythologised as El Dorado. Investors poured in with unbridled enthusiasm, lured by the South Sea Company's partnerships with influential institutions like the Royal Navy and Royal African Company. Subscription shares and the prospect of trading profits fuelled the frenzy further, democratising access to the speculative market.

By 1719, the South Sea Company’s financial entanglements with the government deepened as it took on more debt, issuing increasingly inflated shares. Parliament authorised another £7 million loan as part of the company’s scheme to consolidate national debt. The government supported the company, viewing it as a mechanism to reduce its immediate fiscal burdens while capitalising on speculative profits. Members of the royal court, MPs, and even King George I were shareholders, lending an air of untouchable legitimacy.

Yet beneath the gilded promises lay hollow foundations. The company lacked the expertise for its ventures, particularly in the slave trade, relying on fragile partnerships and outsized ambition. The booming stock market spurred imitations—dubious schemes promising fantastical returns, like companies claiming to extract sunshine from cucumbers. Euphoria turned to mania, and the bubble's eventual burst in 1720 devastated investors, from aristocrats to small-time speculators.

Exchange alley following the crash of the South Sea Company shares in 1720. 19th Century painting by Edward Matthew Ward.

Sir Isaac Newton, the renowned mathematician and physicist, was among the investors. Initially, Newton sold his shares, securing a profit of approximately £20,000. However, he later reinvested at a higher price, ultimately facing significant losses when the bubble burst. Reflecting on this experience, Newton reportedly remarked, "I can calculate the motions of the heavenly bodies, but not the madness of people."

The collapse of the South Sea Bubble had profound implications for the British economy. In the wake of the crash, the British financial system teetered on the brink of collapse. The Bank of England stepped in as a stabilising force, purchasing government debt from distressed investors and injecting liquidity into the market. This intervention, though limited by today’s standards, marked an early assertion of the Bank’s role as a financial backstop. Just like 2008, the central bank which began with limited powers saw increasing influence and sway over the domestic financial system. A good crisis, they say, should never go to waste.

Parliament, recognising the fragility of the financial system, passed legislation to restrict the formation of speculative ventures and tighten oversight of joint-stock companies. However, these measures did little to address the underlying vulnerabilities in Britain’s monetary framework. The financial system, while innovative, was far from perfect.

This expansion of the Bank’s de facto powers and abilities as an early central bank continued into the next few centuries. The 18th century was transformative for the institution as it became a banknote issuer. The first banknotes, known as "white notes," were introduced in 1695 and remained relatively simple in design, consisting of handwritten denominations on paper bearing the Bank's seal. Each note required manual signing by one of the Bank’s cashiers, making the process labour-intensive and the notes highly vulnerable to counterfeiting.

Counterfeiting became a serious issue by the mid-18th century, with forged notes undermining public trust in paper currency. The Bank responded by adopting several innovative security measures:

Watermarks (introduced 1697): Early notes featured rudimentary watermarks as a basic deterrent. By 1801, watermarks became more sophisticated, incorporating unique patterns to make forgery significantly more difficult.

Intricate Designs (1797): The Bank began printing notes with complex, fine-line engravings. These intricate designs were intended to be difficult to replicate with the limited printing technologies of the time.

Standardised Printing Techniques (1725): While initially handwritten, the Bank gradually transitioned to partially printed notes, reducing the risk of human error and forgery. By the late 18th century, fully printed notes became standard, enabling greater uniformity and security.

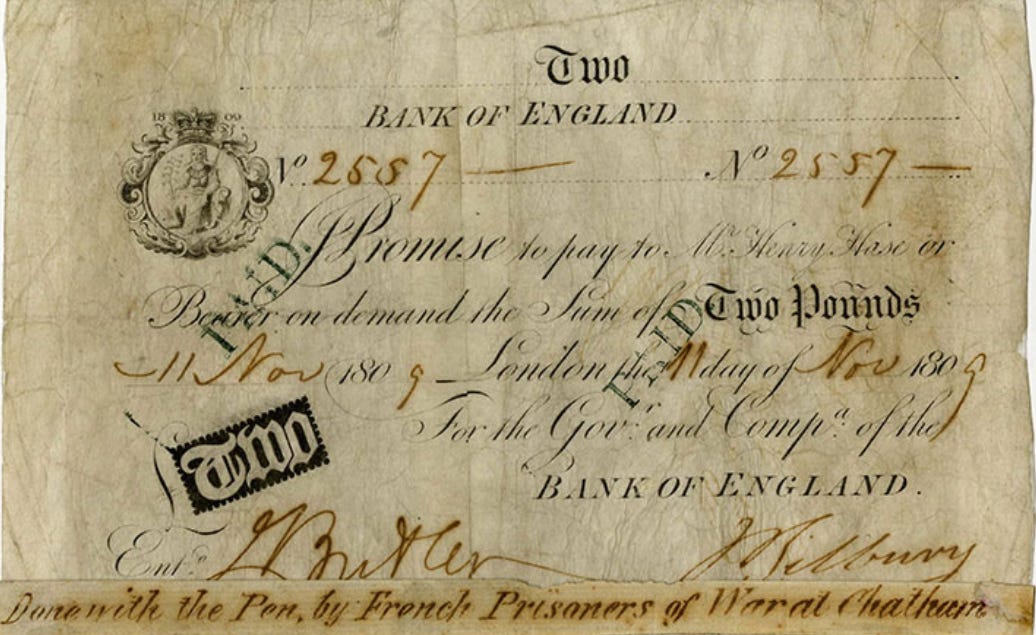

Seized counterfeit £1 bank note stamped with the word “FORGED”

During the Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815), counterfeiting became a tool of economic warfare. The French government is reported to have orchestrated large-scale forgeries of British banknotes, aiming to destabilise the British economy by flooding it with fake currency. These counterfeit notes, often smuggled into Britain via sympathisers or captured ships, created widespread panic and mistrust in paper money. Historian Andrew Odlyzko notes, “The fight against counterfeiting was as much a technological race as it was a legal battle.” Most counterfeiters were engravers but at the time it was possible to create counterfeits by hand.

Hand-drawn counterfeit £2 banknote produced by a French prisoner of war

Counterfeiting was not confined to foreign actors. Within Britain, the economic pressures of the wars, coupled with a lack of employment, drove many individuals to forge banknotes. By the early 19th century, it was estimated that as many as 300 cases of counterfeiting were prosecuted annually in England alone.

This figure likely underrepresented the true scale of the problem, as many forgeries went undetected or unreported. By the height of the counterfeiting crisis, it was estimated that 10% of all circulating Bank of England notes were forgeries. The government did not take kindly to such counterfeiting, between 1805 and 1818, more than 500 people were executed in Britain for counterfeiting offenses.

While the Bank of England’s monopoly on issuing banknotes wasn’t officially formalised until the Bank Charter Act of 1844, its growing reputation as the most reliable institution in an otherwise unstable financial environment was already becoming evident. By the end of the 18th century, Britain was on its way to becoming a global financial powerhouse, and the Bank of England had solidified its position as the bedrock of the country’s financial system. The British banking system was now far more sophisticated, with the Bank of England acting as a steadying force in times of economic turmoil.

A crucial chapter in the Bank of England’s story came with the financing of Britain’s wars, particularly the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars (1793–1815), which ultimately forced Britain off the gold standard in 1797.

Around this time the bank began to be referred to as "The Old Lady of Threadneedle Street,". This nickname originated from a satirical 1797 cartoon by James Gillray. The illustration portrays a distressed elderly woman, symbolising the Bank of England, seated atop a locked chest labelled "Bank of England" and guarded closely. She wears a dress made of £1 banknotes while being accosted by Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger, who is seen slyly picking her gold-filled pockets.

This satirical depiction reflects the strained relationship between the Bank and the government during the Revolutionary Wars against France. As the Pitt administration increasingly drew upon the Bank's gold reserves to fund the war effort, the Bank's ability to maintain payments in gold came under severe pressure. By February 1797, the situation reached a breaking point, leading to the suspension of gold payments. For the first time, low-denomination banknotes in £1 and £2 were issued to address the shortage of coinage and sustain economic activity.

The conflicts required immense funding, with Britain's national debt more than doubling to £679 million by 1815, well over twice the country’s GDP at the time. The Bank of England became the primary financier of the British war effort, expanding its role as a manager of sovereign debt. It issued government bonds and war loans, raising billions in today’s terms to cover the war expenses. By 1813, prices had risen by over 15% annually, with the overall price level doubling during the war period. The peak inflation rate reached 16.3% in 1810.

The Bank had firmly established itself as the country’s debt manager, overseeing interest payments and ensuring the government met its financial obligations while navigating the suspension of gold convertibility. Economists debated the cause: Bullionists like David Ricardo blamed excessive money issuance, while Anti-Bullionists argued external factors like trade disruptions were more significant. By the end of the Napoleonic Wars, the Bank of England had become the dominant institution in British finance, managing nearly all long-term sovereign debt and overseeing the nation’s monetary policy.

As Britain progressed into the 19th century, it experienced a period of rapid economic growth and global hegemony known as the “Golden Age”. It was a period of unprecedented economic growth and global dominance. The Industrial Revolution was transforming the country, and Britain’s empire was expanding rapidly.

The bank’s role in managing the nation’s finances became even more critical during this period, particularly as Britain emerged as the world’s preeminent economic power. The pound sterling became the world’s reserve currency, a status that reflected Britain’s dominance in global trade and finance. The Bank of England’s ability to manage the country’s vast public debt, coupled with its control over the issuance of currency, helped cement Britain’s position at the centre of the global financial system.

The path was not easy, however. In 1866, a massive panic emerged that reignited fears around the vulnerabilities of the fractional reserve banking system. The panic was triggered by the catastrophic failure of Overend, Gurney & Co., a well-established financial firm, and swiftly morphed into a full-blown crisis that shook the entire financial structure of Victorian Britain.

The firm’s meteoric ascent mirrored the era’s boundless ambition, yet its unchecked growth and speculative excess would soon reveal the precarious undercurrents of Victorian finance, culminating in a collapse that shook the nation.

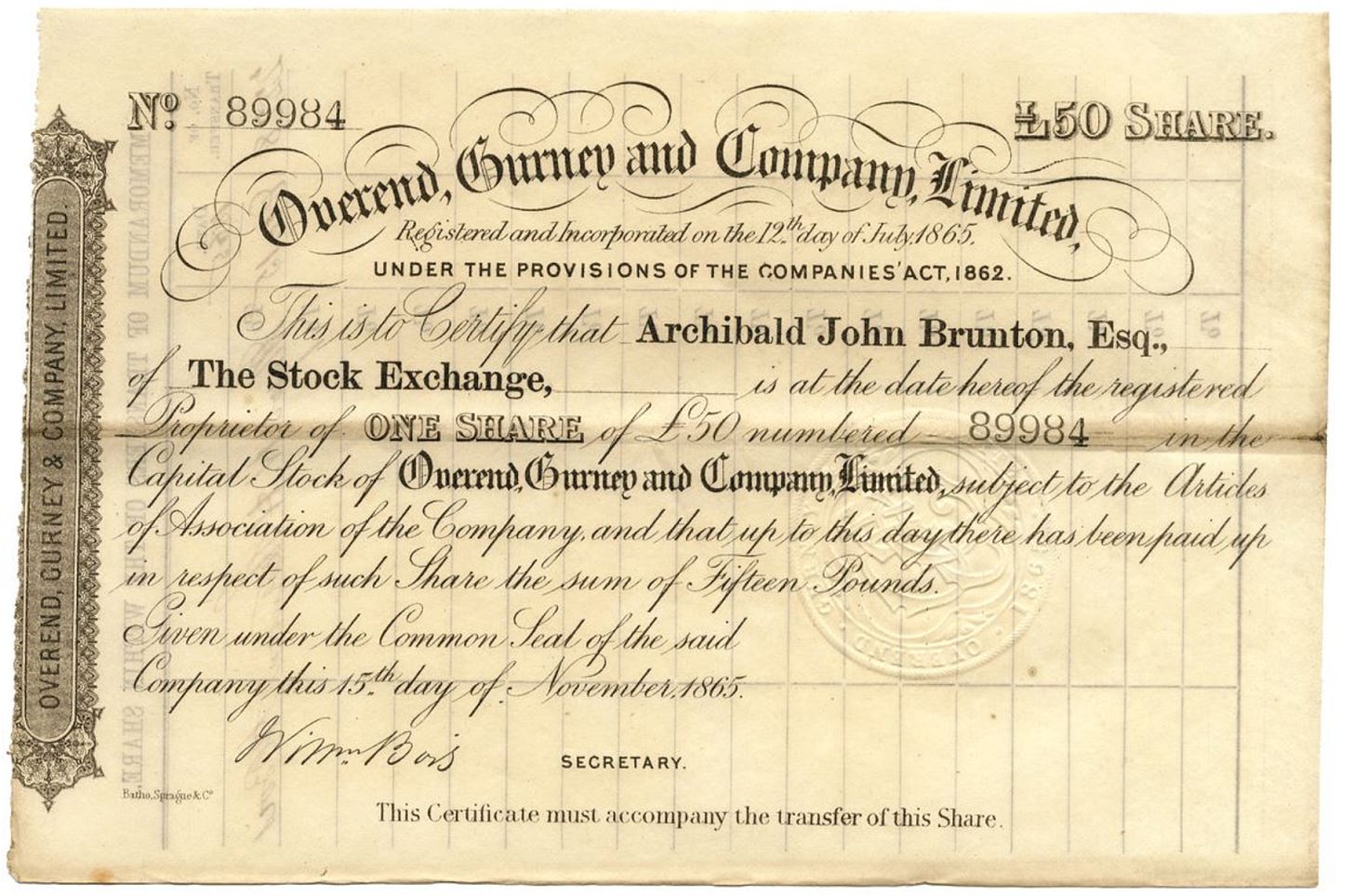

The rise and fall of Overend, Gurney & Co. is one of the most dramatic financial stories of Victorian Britain, encapsulating the perils of overconfidence and unchecked speculation. Founded in 1800 by Quaker banker Samuel Gurney, the firm grew from a small provincial bank in Norwich into London’s premier bill broker by the 1820s, handling short-term commercial paper. By the mid-19th century, Overend Gurney was integral to Britain's expanding industrial economy, processing transactions worth up to £100 million annually equivalent to nearly half the UK’s national debt at the time.

However, the firm’s success bred complacency and risky behaviour. Under the leadership of Samuel Gurney’s successors, Overend Gurney made speculative investments in railways and overseas trade, poorly timed and mismanaged, which drained resources. By 1865, losses reportedly exceeded £500,000 annually. In a desperate attempt to remain afloat, the firm became a joint-stock company, raising £5 million from public capital—though investors were not informed of the firm’s financial peril. Despite this, its speculative ventures continued to unravel.

1865 share certificate of Overend Gurney issued in desperate attempt to raise capital

Amid this turmoil, an anonymous threatening note was discovered on the desk of the Governor of the Bank of England. The note warned that "Overends can pull out every note you have, from actual knowledge the writer can inform you that with their own family assistance they can nurse seven million." This was a chilling reference to the Bank of England’s reserve of notes, which stood at £7.7 million at the time. The implied threat was that Overend Gurney had the means to withdraw almost the entire reserve, potentially sending the Central Bank into a crisis of its own. Despite the threat, the Bank of England refused to alter its stance, maintaining its position against supporting Overend Gurney.

On May 10, 1866, Overend Gurney suspended payments, triggering a panic that would become known as “Black Friday.” The financial sector was rocked, and over 200 banks failed in the ensuing crisis. In response, the Bank of England intervened, acting as a lender of last resort by injecting liquidity into the market—a move that would go on to influence central bank policy, as later articulated by economist Walter Bagehot.

The Bank of England, already struggling with limited reserves, was thrust into the eye of the storm. As the central bank of the empire, it was meant to prevent such crises, but it was also caught unprepared.

In a desperate bid to prevent further contagion, the Bank of England was forced to step in.

To stave off a complete collapse of the banking system, the Bank took several extraordinary actions. The Bank injected liquidity into the market—effectively printing money to restore confidence. In addition to printing money, the Bank also began extending emergency loans to other banks and financial institutions, including struggling banks like Barclays, Lloyds, and Hoare’s Bank. According to contemporary accounts, the Bank’s intervention was nothing short of heroic. The Times described it as "a lifeline thrown into a turbulent sea," praising the Bank’s swift actions, but it was clear that the decision to flood the market with liquidity came with its own risks.

The public's reaction was a mixture of fear, confusion, and anger. As banks faltered, panic spread through the streets of London. The city’s financial district was thrown into chaos, with the middle and working classes worried about the safety of their savings. Newspaper reports from the time are filled with horror-stricken accounts of people scrambling to withdraw their money, creating a palpable sense of dread and worsening the financial contagion.

Front cover of CLEVELAND DAILY LEADER, Ohio, May 22, 1866

At the same time, many criticised the Bank of England. The Economist blamed the Bank for allowing the crisis to unfold in the first place, writing, "The Bank’s blind faith in the solvency of a reckless banking house has now brought the whole Empire to its knees." The Bank’s failure to intervene earlier in the crisis was viewed as a catastrophic misstep. As for Overend, Gurney & Co., the collapse was seen as a manifestation of unchecked greed and speculative madness—an example of the dangers lurking within the financial system. Many in the press felt that the government and the Bank should have stepped in sooner to prevent the excessive risk-taking that led to the collapse.

Despite the immediate panic, the Bank’s swift actions helped restore order. Within weeks, the worst of the panic had passed, and the Bank had managed to stabilise the financial markets. However, the damage to public trust was lasting. The Bank’s intervention, though ultimately successful, raised difficult questions about the moral hazard of bailing out failed financial institutions. Critics feared that this would set a dangerous precedent, one where speculative firms would take on ever-greater risks knowing that the Bank would always step in to prevent catastrophe…

In the years following the crisis, discussions intensified about the need for stronger financial regulation. Bagehot, writing in his Lombard Street in 1873, would famously argue that in times of crisis, the Bank should lend "freely, at high rates, to solvent institutions." The events of 1866, however, highlighted a serious flaw in the financial system: the absence of clear rules governing bank conduct and the government's response to systemic risks. Overend, Gurney’s collapse was a dire warning that Britain's laissez-faire approach to finance needed reform.

However, the bank’s influence still wasn’t limited to peacetime prosperity. During World War I, the Bank of England was once again called upon to finance Britain’s war efforts. In 1914, as the war escalated, the British government issued a war loan to help fund the conflict. On November 23, 1914, a glowing report appeared in the Financial Times, claiming that the war loan had been “oversubscribed” and that applications were “pouring in.” It was described as an “amazing result” that demonstrated the financial strength of the British nation. There was just one problem: none of it was true.

Behind the scenes, the Bank of England had struggled to find enough investors to cover the war loan. In fact, the government had turned to the Bank of England for more than £100 million in financing to make up the shortfall. The Financial Times had played its part in convincing the public that the war loan was a success, thereby shoring up public confidence at a critical moment. While the truth eventually came to light, after an apology was issued in 2017, the episode highlights the powerful role that the Bank of England played in not only managing the nation’s finances but also shaping public perception.

In Lords of Finance, John Maynard Keynes famously predicted that World War I wouldn’t last more than a year because the countries involved simply couldn’t afford to sustain it. According to his reasoning, the economic strain would be too great, as all sides would quickly exhaust their financial resources.. Yet, nations found ways to defy the financial odds, stretching their resources and borrowing heavily, which fuelled the war far longer than expected and set the stage for the economic turmoil that followed.

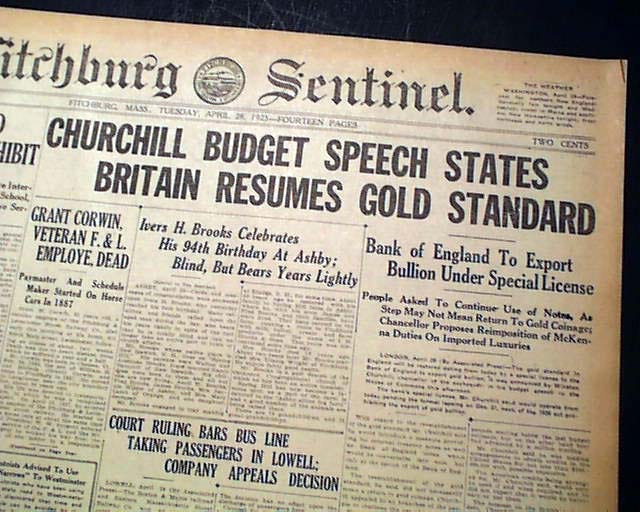

In the immediate aftermath of World War I, Britain found itself grappling with profound economic challenges. The war had wreaked havoc on the nation’s finances, leaving it with significant debt and a diminished export market. Despite these hurdles, the government sought to restore the pre-war financial order by returning to the gold standard in 1925. Winston Churchill, then Chancellor of the Exchequer, championed this move as a symbol of stability and Britain’s enduring global leadership. However, this decision would prove controversial and ultimately disastrous.

The gold standard tied the value of the British pound to a fixed quantity of gold, but Churchill’s government set the rate at the pre-war parity of $4.86 per pound. This overvaluation rendered British exports uncompetitive, exacerbating unemployment and slowing industrial recovery. Keynes fiercely criticised this move in his essay The Economic Consequences of Mr. Churchill, arguing that it would cause deflation and stagnation—predictions that tragically came true.

Deflationary pressures mounted, squeezing industries, and shrinking domestic demand. The situation worsened during the Great Depression of the 1930s, as global economic contraction crippled trade and finance. Britain’s rigid adherence to the gold standard restricted monetary flexibility, preventing necessary adjustments to address the crisis.

By 1931, the system had reached a breaking point. A series of financial shocks, including the failure of a major Austrian bank and a speculative attack on the pound, forced Britain to abandon the gold standard. The government devalued the currency, allowing it to float freely for the first time in centuries. This marked a dramatic shift in monetary policy, as the pound’s value now reflected market conditions rather than gold reserves.

The abandonment of the gold standard was met with immediate criticism and relief. While it tarnished Britain’s image as a financial superpower, the decision ultimately provided much-needed flexibility. The pound’s depreciation helped restore competitiveness, boosting exports and relieving some of the economic pressures. Nevertheless, the episode signalled the decline of sterling’s dominance in global finance, as nations increasingly turned to the U.S. dollar and other currencies for stability. Churchill later lamented his decision, admitting he lacked the economic expertise to foresee the consequences.

After World War I, the British pound gradually lost its status as the world's dominant reserve currency, but this process took several decades and was deeply influenced by both World Wars and economic changes. Before WWI, the British Empire's economic power and global reach had cemented the pound sterling's status as the world’s primary reserve currency, a symbol of Britain's vast trade network and financial influence. However, the war's financial strains, combined with the enormous debts Britain incurred, began to weaken this position.

The decline of the British pound’s dominance culminated with the rise of the U.S. dollar as the global reserve currency at the Bretton Woods Conference in 1944. Despite John Maynard Keynes advocating for a new international currency, the Bancor, which he believed would better serve global trade, the U.S. insisted on using the dollar, which was pegged to gold. Keynes's visionary Bancor never materialised, and the America took center stage, becoming the foundation of the new global financial system.